Francis Bacon was a man whom I both knew and did not know. Born in Dublin in 1909, certainly Irish by birth, if not by blood. He had the Irish love for gambling, drinking and the perpetual desire to be somewhere else. I first met Bacon outside the Marlborough Magistrates Court, London 1971. The Daily Telegraph published a story ‘Irish Artist on Drug Charge’: the artist was acquitted. In his defence, he told the Magistrate that he could not have smoked cannabis found in his home because he was asthmatic.

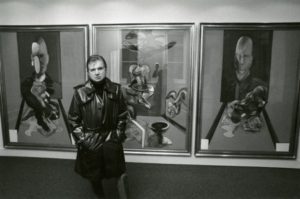

Over the next 20 years I would photograph him on numerous occasions in London and, at his invitation, in Paris 1977 for his show at the Claude Bernard Gallery on the rue de Beaux Arts which became a busy street some 24 hours after the show’s opening had attracted, according to police estimate, 8000 viewers. Some six years earlier the French did him the great honour of putting on a retrospective show of his work at the Grand Palais. This is the kind of consecration that Bacon was accorded in a city that gave birth to photography in 1839 when Louis Daguerre exclaimed from the balcony, “I have seized the light, I have arrested its flight!”

Bacon came to love Paris from his first visit in the 1920s when he saw a show of paintings by Picasso which triggered in him the motivation to paint: like many others who have seen the paintings of Francis Bacon. You become either fascinated or repelled or both, by their power and effect on the emotions.

During the 1970s I would see Francis Bacon and exchange courtesies in Soho, London’s Bohemian Quarter with its strip joints, coffee shops and pubs. In those days Soho was full of drinking clubs. They existed partly to quench the thirst of afternoon drinkers, journalists, petty criminals, doctors, artists and writers at a time when the pubs were obliged to shut from 3 to 5.30pm. I remember those days very well. Working as a staff photographer for the Evening Standard in the early 60s, I spent much of my spare time in Ronnie Scott’s, The Marquee Club, The Colony Room and The York Minster, known now as The French.

I have fond memories of Francis sitting alone, a few years before he died, having lunch and liquid refreshment in the most exquisite Bibendum Restaurant in what was the Michelin Building at the intersection of the Fulham Road by the end of Pelham Street, a ten minute walk from the Bacon Studio at 7 Reece Mews, South Kensington. By that time I had photographed the artist many times in London and in Paris. It must be said that Valerie Beston from the Marlborough Fine Art, who Bacon trusted and depended on to make judgement on who he should and should not see, helped me to make contact with Bacon and Graham Sutherland whose wife Kathleen was Irish.

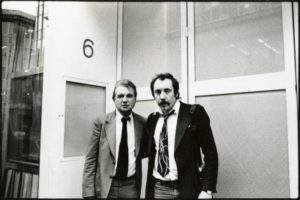

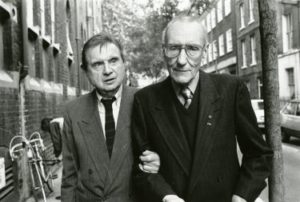

Bacon had given me his private home phone number. I remember calling him on the day of his retrospective at the Tate Gallery in 1985 and asking what time he would be at the Tate as I wanted to photograph him outside on the steps of what was then the original Tate Gallery, now renamed Tate Britain. As always, his manner over the phone was welcoming and he said I should be there about 2 o’clock, as he would arrive with friends. Francis arrived at the Tate just after 2 o’clock with friends Richard Chopping and Denis Wirth-Miller for what was then his second retrospective at the Tate Gallery. The press pack were already in the gallery. I was pleased to have my exclusive outside this illustrious building. All through the 80s I was photographing another Dubliner, Samuel Beckett, who was born some three years before Bacon. I became engulfed by Bacon and Beckett. They were hypnotic. I had hoped that I might get them both together in a photograph. I asked Francis who was very well aware of Beckett as Beckett was of Bacon. Francis Bacon told me that there were no messages in his paintings and no connection with Beckett. Like Beckett, he did not lie. David Sylvester the art critic created through his interviews with Bacon the cottage industry on which writers to this day so heavily depend. I remember having a pot of tea with David at the Dublin Writers Centre in 2001, after I took a photograph of him outside the Hugh Lane Gallery, he was telling me how photographers would approach him to take his picture in the hope that he would introduce them to Bacon. Many photographers did photograph the artist. He was happy in the company of photographers, less so with journalists. I do remember Bill Brandt telling me about his marvellous photograph of Francis Bacon on Primrose Hill, which Bacon told me some years later he hated. Photography was the salient influence in his work. He would often stop at the automatic photo booth in South Kensington tube station to pose for a strip of four passport sized portraits which he would work from. Recently in London I passed the now closed door that was the Colony Room, where once I heard the cry “Champagne for my real friends and real pain for my sham friends”, Bacon’s frequent toast which he displayed with an icy, ceremonious politeness.

Those who knew Francis Bacon are diminishing in number, at a time when exhibitions of his work worldwide are always a major artistic event. He would immortalise Muriel Belcher with his passion for triptychs in Three studies of Muriel Belcher (1966). Muriel was the greatest of Soho characters from 1948 when she opened the Colony Room Club. Francis Bacon would be her prized and most famous member. Like Samuel Beckett, Bacon had a bleak vision of human existence: where Beckett would write it, Bacon would paint it.

I want to thank Mr Majid Boustany founder and director of the Francis Bacon MB Art Foundation in Monaco for inviting me on a tour of the Foundation, which is a must for scholars and researchers interested in retrospective analysis of the artist. Among the items are letters, photographs, paintings, books about Bacon in all languages, and a Batchelors’s paint splattered butter beans can with assorted large brushes that were used to create a unique work of art with great inventiveness.

I did have a show of photographs, ‘Bacon, Beckett and Burroughs’ at the October Gallery, London February 1990. As we say in Ireland, ‘their likes we will never see again’.

John Minihan

Photographer