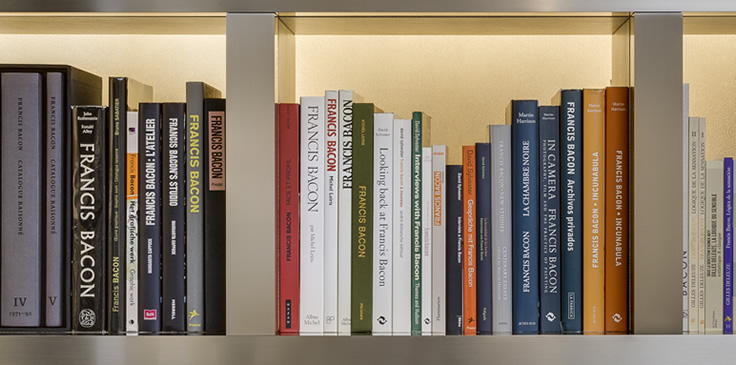

Recreation of Francis Bacon's library

The Francis Bacon MB Art Foundation houses a recreation of Francis Bacon’s personal library containing copies of almost 500 books (in the same editions), magazines and newspapers found in the artist’s studios, and especially at 7 Reece Mews in London.

View selected publications from the Foundation’s recreation of Francis Bacon’s library:

Phenomena of Materialisation

Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co Ltd.

1920

One of the most peculiar books found in Bacon’s studio was Phenomena of Materialisation: A Contribution to the Investigation of Mediumistic Teleplastics (1920), the English translation of a German book by Baron von Schrenck-Notzing, a doctor, published in 1914.

The book is an account of seances and manifestations of spirits, illustrated with photographs. In the telepathic seances, one person was enclosed in a circular tent-like structure partly hidden behind a curtain. The ghostly figures that appear in Bacon’s art from the 1940s to the 1970s were inspired by von Schrenck-Notzing’s images. The left-hand panel of one of Bacon’s most famous paintings, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), was based on a photograph of the famous medium Eva Carrière from Phenomena of Materialisation.

Eisenstein at Work

Methuen

1985

Bacon often stated that he would have liked to be a film director if he had not been a painter, and the influence of cinema on his art is undeniable. For instance, his first screaming popes were inspired by stills of the screaming nurse from the ‘Odessa Steps’ sequence in Sergei Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin.

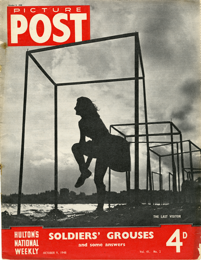

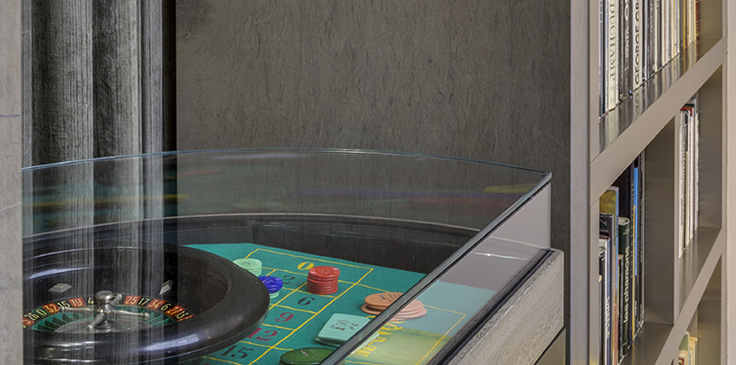

Picture Post

In interviews, Bacon often said that he looked at all kinds of photographs. He saw them as reference points and potential triggers for ideas for his work.

Picture Post was among the various English and French magazines the artist used as source material. The transparent three-dimensional structure on the cover of this issue of the magazine appears in several of Bacon’s paintings, with figures seemingly trapped in the transparent cage like animals in captivity. The cage structure focuses attention on the figure and creates a sense of unease, confinement and claustrophobia.

The Human Figure in Motion

Dover Publications Inc.

1955

In 1949, Denis Wirth-Miller drew Francis Bacon’s attention to Eadweard Muybridge’s chronophotographic images of humans and animals, held by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

These studies, which anticipated cinematography, became essential working material for Bacon from the 1950s onwards. He transformed the meaning of Muybridge’s images by grafting his own face or body or those of close friends and lovers onto Muybridge’s human figures. In an interview with David Sylvester, He said of his use of Muybridge photographs, ‘I very often think of people’s bodies that I’ve known. I think of the contours of those bodies that have particularly affected me, but then they’re grafted very often onto Muybridge’s bodies. I manipulate the Muybridge bodies into the form of bodies I have known.’

Velasquez

Spring Books

1965

Bacon considered Diego Velázquez to be the greatest of all artists. He said of Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, ‘I’ve always thought this was one of the greatest paintings in the world and I’ve had a crush on it.’ He was so obsessed and haunted by it that he produced over fifty variations of it.

Introducing Monkeys

Spring Books

1957

In the early 1950s, Bacon visited his mother and sister in South Africa, where he spent time observing the movements and behaviour of wild animals.

From a very early stage in his career, his paintings deliberately sustained an ambiguity between images of humans and animals. He even went so far as to superimpose the features of an ape on a human figure.

In an interview with David Sylvester, Bacon said, ‘Animal movement and human movement are continually linked in my imagery of human movement.’

Positioning in Radiography (Eighth edition)

Ilford Ltd.

1964

Bacon’s predilection for shocking imagery is confirmed by his collection of medical books.

Kathleen C. Clark’s book Positioning in Radiography (1939), which contains photographs of people being X-rayed, provided Bacon with a stock of evocative images and a catalogue of distinctive anatomical distortions. Its plates inspired several of his circled areas, arrows indicating direction and unconventional limb positions.

A Pictorial History of Boxing

Spring Books

1959

Bacon’s interest in sporting activities was purely academic. Illustrated books on cricket, boxing, martial arts, tennis, swimming, football and golf were found in his studio. His main interest in these publications was to study the human body in action, in movement. The main figure in the right-hand panel of Crucifixion (1965) was directly based on pictures of the boxer Max Schmeling, taken as he was falling, from Nat Fleischer and Sam Andre’s A Pictorial History of Boxing (1959).

The Acanthus History of Sculpture: Ancient Egypt

The Oldbourne Press

1960

Bacon had a high regard for the art of Ancient Egypt ‒ the civilisation that most fascinated him. He visited Cairo in 1951 and produced four paintings on the theme of the Sphinx between 1953 and 1954.

He said of Ancient Egyptian art, ‘The figures are extremely vivid and realistic, especially the statues from the Old Kingdom, with those cursorily painted faces, but where you have an extraordinary presence. I would like my painting to be present, with no underlying message.’

The Drawings of Michelangelo

Thames and Hudson

1971

Bacon owned more books on Michelangelo than on any other artist. He described the Italian master as the greatest of all draughtsmen, adding that his nudes were the most voluptuous in the history of the visual arts. From an early stage, Bacon’s work was inspired by the great Renaissance artist’s sculptures and drawings.

Collected Poems 1909-1962

Harcourt Brace & Company

1963

The works of T. S. Eliot, an American poet who took British nationality, inspired several of Bacon’s paintings including Triptych 1967, often entitled ‘Triptych inspired by T. S. Eliot’s Sweeney Agonistes’. What Bacon appreciated most in Eliot was his ability to analyse human passions and behaviour. He remarked of Eliot’s poems, ‘I really read things which bring up images for me. … It happens very much with Eliot. … I don’t say that these images are really to do with the poems of Eliot or even with the plays of Shakespeare, but they open up the valves of sensation for me and so images drop in like that.’

The Oresteian Trilogy

Penguin Books

1956

After seeing T.S. Eliot’s 1939 play The Family Reunion, which was based on Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy, on stage several times, Bacon was impelled to find out more about Greek tragedy. He explored the work of Aeschylus and became fascinated by the famous trilogy about the House of Atreus, which suggested more images to him than any other text. His favourite quotation from the Oresteia was ‘The reek of human blood smiles out at me.’

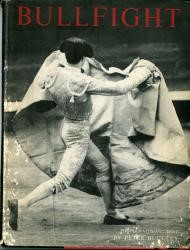

Bullfight

Simon and Schuster

1958

During various trips to the South of France and Spain in the 1960s, Bacon began to develop an interest in bullfighting. After reading Miroir de la Tauromachie (1938) by his friend Michel Leiris, of which the author gave him a copy, he became fascinated by the whole atmosphere and ritual. For Francis Bacon (interviewed by Michael Peppiatt in Art International, Autumn 1987), bullfighting was ‘all about death, but it’s about death in the sunlight, and for me that does conjure up all kinds of images.’

In 1969, Bacon painted first Study for Bullfight No. 1, then two other versions. Bullfighting imagery inspired other works, including Study of a Bull (1991), the last painting completed by the artist.