Foundation Focus

At the Foundation’s invitation, art historians and other scholars, photographers, artists and friends of the painter discuss a wide range of topics related to Francis Bacon’s art, life and working practice.

James Birch

Art Dealer and Gallery Owner

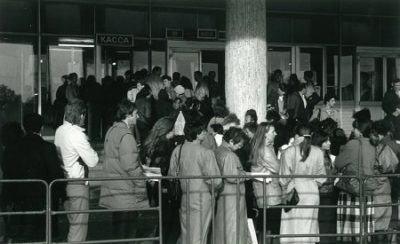

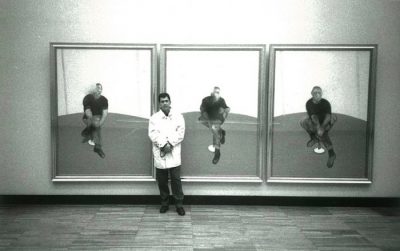

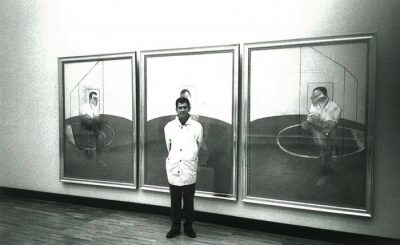

Francis Bacon Exhibition Moscow 1988

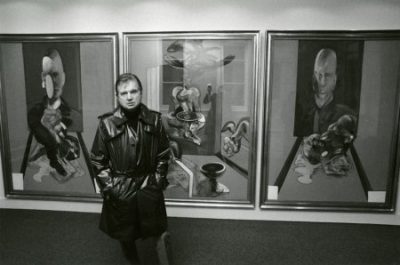

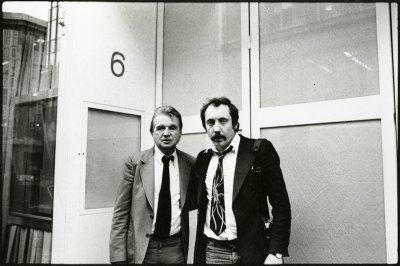

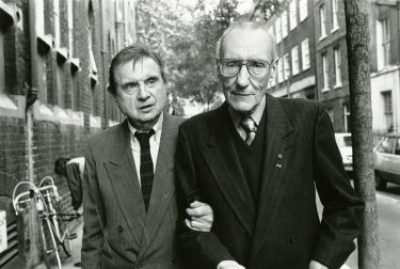

In March 1985 Mikhail Gorbachev became First Secretary of the Soviet Union. Things were beginning to change. In December 1985 I was running a gallery in the King’s Road showing young artists, including Grayson Perry and the Neo-naturists. I wanted to show my stable of young artists in New York. At a party a friend of mine suggested I take them to Moscow instead. I rang him the next day and he suggested I go to the Soviet section of UNESCO in Paris. In Paris, I met the UNESCO representative, a Mr Klokov. Over lunch he gave me the name of the one person who could be of assistance within the Union of Artists of the USSR, which dealt with the work of living painters. Six months later I received a telegram inviting me to Moscow to discuss my proposal– this was July 1986. I went with the delegation of other persons interested in doing negotiations with Russia as at the time that was the only way in. Within a couple of days of arriving in Moscow I realised it was impossible to show my stable of artists but the protocol was that I had to visit many artist’s studios. Over the course of discussions and much vodka I asked, which artist they would most love to see from the UK. They all replied “Francis Bacon”. I asked Klokov if an exhibition of Francis Bacon would be acceptable and popular in the USSR– he thought it would be. A few months after returning to London, I opened a new gallery on Dean Street Soho (Birch & Conran) showing an exhibition of British Pop Art. That evening Francis Bacon arrived with Denis Wirth-Miller. Over dinner later, I asked Francis if he would like to have an exhibition in Moscow, and he said “Oh I would love to”, he had just had bad reviews in the USA. The next day I rang Klokov in Moscow- which you had to book a call five hours in advance to do.

Initially Bacon was worried about obtaining works from private owners who might object to an exhibition in the USSR but this seemed not to be a problem. The exhibition was a small retrospective comprising of 22 paintings including diptychs and triptychs from all periods of his work. His gallery, Marlborough Fine Art, London, were delighted. The selection was made largely by Bacon and Miss Beston of the Marlborough Gallery, although a few of the works were rejected by the first secretary of the union of artists as they were thought to be too pornographic.

It opened on the 22nd of September, 1988, at the Union of Artists’ hall in Moscow (A similar sized venue to the Hayward Gallery in London). This was the first time that a living Western artist of the first rank had been exhibited in the USSR. The convoluted processes by which this came about, sheds an interesting light on prevailing, very different, current Soviet attitudes towards art and its organisation.

Francis himself was looking forward to the opening as he always acknowledged the work of Eisenstein’s films; notably the nurse on the Odessa steps sequence in Battleship Potemkin, which was one of his sources for his portraits of the Screaming Popes, he was also learning Russian on a language course by cassette. He could have pulled the plug on this exhibition at any moment, due to various costs and health issues, but he was determined for it to happen, and had full trust in my project as I had known him since I was a child. Sadly, due to ill health, he never came to it but wanted to hear all about it when I returned from Moscow.

The exhibition was a huge success.

Photo and © James Birch

Photo and © James Birch

Photo and © James Birch

Carrie Pilto

Art Historian, Independent Curator

Guy Bourdin: Francis Bacon’s Painting 1946 in the mirror of fashion photography

“Je ne suis pas un metteur en scène. Juste un ajusteur du hasard. (I’m not a director. Just an adjustor of chance.)”

Guy Bourdin

A photograph shows a young couple shrouded with a black umbrella, mischievously miming Francis Bacon’s Painting 1946. The image belongs to the archives of fashion photographer Guy Bourdin (Paris 1928-1991) and shows the then protégé of Man Ray with his partner Solange in 1950s Paris, where Bourdin may well have seen Painting 1946 when it was shown in the British section of a UNESCO sponsored post-war exhibition of contemporary art at the Musée d’art moderne. While it is a playful self-portrait, it testifies to Bourdin’s early interest in Bacon’s work, a fascination that comes through in his fashion photographs and is sustained by the number of publications on Bacon contained in his library, which I was fortunate to study a few years after he passed away.

Bourdin references a breadth of Bacon’s paintings over his thirty-year career, but Painting 1946 plays a seminal role. Bourdin repeatedly appropriated elements of its vocabulary: the black umbrella, the isolated figure enclosed in a room or a cage-like structure, butchered meat, the artificially vivid color background, the uncanny assemblage of disparate components “by chance”, transforming them into his own signature style. The painting thus appears to form a basis for his photographic language, both formal and spiritual.

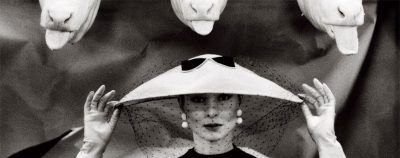

The influence of Painting 1946 is clearly visible, for instance, in Bourdin’s very first commercial commission, a series on spring hats for the February 1955 issue of Vogue France.

Set at a butcher shop in the Rue de Buci, one photo in the series shows a model standing before suspended carcasses of flayed rabbits. Her dark, wide-brimmed hat shadows her dead expression and echoes Bacon’s masculine, umbrella-covered figure before the beef carcass in Painting 1946. The rhythm of swags formed by the rabbits’ legs, between their fur-clad back paws, recalls the classical frieze of garlands hanging from atop Bacon’s composition. Behind the display of meat, in the background of both works, two window shades close off all perspective and isolate the scene. To capture it, Bourdin used a heavy wooden camera with large plates. His focus on the flesh is sharp and detailed; the underlying message is merciless: “… we are meat, we are potential carcasses”, as Bacon would often repeat in interviews[1]. Seen in retrospect, Bourdin’s image reveals itself as his fashion manifesto: a darkly humoristic momento mori, launching a snub at the vanity of the luxury industry he represents.

Aside from formal borrowings, Bourdin appears to identify with Bacon at the level of the conception of the picture. Bacon described Painting 1946 as his most unconscious work. He said to David Sylvester: “I was attempting to make a bird alighting on a field. … but suddenly the line that I had drawn suggested something totally different and out of this suggestion arose this picture. I had no intention to do this picture; I never thought of it in that way. It was like one continuous accident mounting on top of another.” Bourdin was surely remembering Bacon’s interview with Sylvester when he gave a rare interview of his own to Photo magazine in 1987, telling: « I’ve never considered myself the one responsible for my images. They are just accidents.[2] »

Like the painter, Bourdin would preconceive and sketch out the scenes he intended to portray, but in the process of shooting allow, indeed even wait for, a providential surprise to intervene, looking for something to disorient his own vision[3]. To Bacon’s assertion: “I want a very ordered image, but I want it to come about by chance[4]”, Bourdin once reverberated: « Je ne suis pas un metteur en scène. Juste un ajusteur du hasard.[5]” (I’m not a director. Just an adjustor of chance.) Both artists can be seen here to adhere to the idea, dear to the Surrealists, of hasard manipulé: a belief in the necessity of integrating chance and accidents to give art a new, unforeseen quality. Bacon explained that this process drives the image to a superior level, beyond conscious illustration. This is exactly the quality for which Bourdin’s photographs would become sought after in his provocative advertisements and fashion spreads, and now again, as his work becomes privately and publicly collected. The belief in ‘manipulated chance’ lifts Bourdin’s work from that of a commercial artist or illustrator; indeed, for Bacon, chance is precisely what distinguishes the artist from the artisan.

While the previous picture did not make it into the magazine, a similar one did. A model wearing a broad hat and veil pulled down over her face poses under a row of pale calf heads hanging forsakenly from hooks, their tongues dangling. Her human head is aligned precisely under that of one of the bovines, suggesting their interchangeability, and recalling Bacon’s sentiment: “If I go into a butcher’s shop I always think it’s surprising that I wasn’t there instead of the animal.[6]” A chunk of meat lies beside her on the counter showing its price per pound, in a disposition that evokes the cut of beef presented to the left of the dark-suited man in Painting 1946. This last detail was cropped out when the photo was reframed for print. (The price of fresh meat associated with the woman’s body was perhaps a step too far for Vogue’s readership). Despite the censorship, the photograph produced for Bourdin the desired effect of sticking his tongue out. Michel Guerrin noted that the Vogue article, aptly titled « Chapeaux-choc », provoked “emotion, insult letters, subscription cancellations and threats of advertisers[7]”.

In transposing Painting 1946’s underlying message to fashion’s sacred temple, the pages of Vogue, Bourdin began a sensational habit of infiltrating Bacon’s dark imagery into the psyche of the style conscious. Unbeknownst to most, many of Bacon’s paintings live on in fashion magazines.

[1] David Sylvester, Interviews with Francis Bacon 1962-1979, Thames & Hudson, London, 1980.

[2] Guy Bourdin cited in « Le Luxe est irréverence », Photo n°235, April 1987, author’s translation.

[3] “Une compétition non dite s’instaurait entre nous pour l’épater, pour trouver le je-ne-sais-quoi déclencheur. Il suffisait de le surprendre…”, Susan Moncur cited in Magali Jauffret, “Guy Bourdin l’œil absolu ”, Connaissance des arts, Paris, spécial photo n°1, July-October 2004, pp. 55-77.

[4] David Sylvester, op. cit.

[5] Guy Bourdin cited in « L’Hommage de Photo à notre ami Guy Bourdin », Photo n°284, May 1991.

[6] David Sylvester, op. cit.

[7] Michel Guerrin, “Une image de Guy Bourdin n’est jamais sereine” in Exhibit A, n.p. (author’s translation).

© The Guy Bourdin Estate 2016 / Courtesy of Louise Alexander Gallery

© The Guy Bourdin Estate 2016 / Courtesy of Louise Alexander Gallery

© The Guy Bourdin Estate 2016 / Courtesy of Louise Alexander Gallery

Margarita Cappock

Deputy Director & Head of Collections, Dublin City Gallery

Revelations from Bacon’s studio: contemporary art

Much has been written on Francis Bacon’s relationship with the art of the past and how he borrowed or stole from great masters such as Velázquez, Michelangelo, Ingres, Degas and Van Gogh. Bacon’s predilection for these artists is reflected in the studio contents with many reproductions of the work of all these artists found. A less publicised dimension is Bacon’s relationships with and interest in younger, less prominent artists, many of whom were only establishing themselves while Bacon was at the pinnacle of his own artistic career. Bacon was exceptionally visually literate and was constantly looking at and absorbing visual material regardless of where he encountered it. Throughout his life Bacon was open to new developments in art and the contents of his Reece Mews studio are revealing in terms of the loose leaves from catalogues and books, interventions, mounted images and correspondence and material relating to many contemporary artists– Ernest Pignon-Ernest, Vladimir Velickovic, Jacques Monory, Duane Michals, Clare Shenstone, Vito Acconci, Paolo Gioli, Franta, Peter Klasen, Eddy Batache, Marie-Jo Lafontaine and Don Bachardy. Obviously it would be facile to suggest that Bacon was influenced equally by all the artists whose material was found in the studio yet it is clear is that he was alert and receptive to new developments in art. The studio contents also reveal that Bacon engaged at a very direct level with some of these artists (and photographers) by meeting them, corresponding with some, posing for them and occasionally commissioning works from them or requesting that they send him material.

It is apparent that with many of the artists whose work appealed to Bacon or caught his imagination, aspects of their work mirror Bacon’s own fascinations and preoccupations – bodies contorted in motion, heads with open mouths or the human body undergoing some form of stress or anguish. Certain formal qualities and motifs also appealed, for example, images of doors or isolated street scenes. Some of the artists shared similar interests or concerns such as a passion for photography, particularly photography of the body in motion such as the photography of Eadweard Muybridge, Jules Etienne Marey and Thomas Eakins (admired by Vladimir Velickovic, Duane Michals, Vito Acconci and Paolo Gioli) or an obsession with cinema and cinematic techniques as is the case with Pignon, Gioli and Michals too. There is a definite preference for French artists or artists based in France and many were represented by Galerie Lelong or Galerie Maeght, two galleries Bacon himself exhibited with during his life. Of course Bacon loved Paris and had a studio there from 1975 to 1987. He spoke French, was close friends with many French intellectuals and writers and exhibited there regularly. With the exception of Damien Hirst and Clare Shenstone, there is very little material on or reference to younger British artists amongst Bacon’s found source materials.

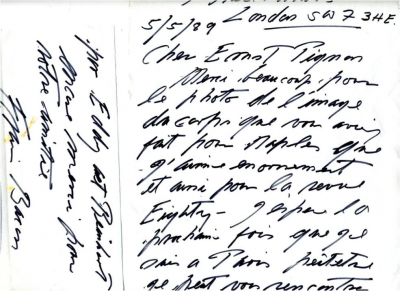

One of the more significant collections of images is of the work of the French artist Ernest Pignon-Ernest (born Nice, 1942) who since 1966 made the street the subject and setting of his ephemeral works of art, which echo both historical and contemporary events. In an interview with the French newspaper, Libération, when Bacon was asked which painters he liked, he immediately singled out Pignon saying “in France you have Ernest Pignon-Ernest”. Bacon took an active interest in Pignon-Ernest’s work and sought some images of his work directly from the artist. Although both artists exhibited with Galerie Lelong in Paris, the two never met, although letters in the studio indicate that attempts were made to meet in person. Pignon-Ernest explained in correspondence with me that two art critics who had just interviewed Bacon in London, visited Pignon and informed him that Bacon knew and was interested in Pignon-Ernest’s work. Bacon had seen a photograph of Pignon-Ernest’s Naples interventions and asked the critics if they could ask him to send him a photograph of a work entitled, Le Soupirail, which was an image of a body emerging from a grill. Pignon-Ernest spent eight years creating and attaching several hundred images to buildings throughout the city of Naples, borrowing from Classical mythology and early Christian iconography, to evoke Naples’s rich and tumultuous history. The Naples piece that Bacon admired was inspired by a study by the 17th century Italian artist, Luca Giordano, for La Peste. After Bacon received this photograph he wrote to Pignon-Ernest and told him that he had, in fact, followed his work since he discovered images that Pignon-Ernest had made in Grenoble in 1976. These Grenoble works looked at the degradations of the workers caused by industry. The use of large directional arrows by Pignon-Ernest recalls the work of Bacon.

Most of the art magazines found in Bacon’s studio were French, for example, Opus International, Repères – Cahiers d’art contemporain (Galerie Lelong) and Chronique de l’art vivant (Maeght publications). Many have pages torn out and many of the images from these French art magazines date from 1976/77, a time when Bacon had a studio in Paris. The French writer, poet and artist, Alain Jouffroy, whom Bacon knew, was a friend of some of the artists that feature in Bacon’s material. Alain Jouffroy was a friend of Velickovic whom Bacon met and whose studio he visited. He was also a friend of Peter Klasen, (born 1935), a German artist based in France since 1956 and a page torn from Opus International found in Bacon’s studio features the work of Klasen. In 1971, the same year as Bacon’s exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris, Klasen achieved great success through the exhibition “Ensembles et Accessoires”, a retrospective presented at ARC at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris. One wonders if Bacon saw this show which featured depictions of objects such as surgical utensils, baths, toilets and wash hand basins. Again these motifs resonated with Bacon who also collected images of bathrooms from plumbing catalogues.

The purpose of this short piece is to provide a flavour of the artists whom Bacon sought direct contact with and those artists whose work he commented upon. I am currently engaged in further research on this fascinating aspect of Francis Bacon’s studio contents.

Clare Shenstone

Artist

My time with Francis Bacon

My contact with Francis Bacon started in 1979. That was the year that I exhibited my degree show, at the Royal College of Art.

I was there at nine every morning. On the third day of the show, my tutor rushed over to me.

He handed me a piece of paper with a telephone number written on it. He said, “You must ring this number at exactly 11 o’clock. You’ve had a very distinguished visitor, and he wants to talk to you.” I thought this must be some kind of joke. But he said “This is genuine. Just ring the number.”

At exactly 11 am, I telephoned the number. Francis Bacon answered my call.

Apparently, he had arrived at the show at 8am, to collect some cases of wine. While he was waiting for them to bring it down, he looked around the exhibition. He saw my work – a series of cloth heads. I had been perfecting this way of showing the human face, by using something as flexible as skin, into which I molded the facial features…

“I adore your work”, he told me.

I said, “My gosh! Well, I think you’re the best artist alive in the world today.”

He said, “Great minds think alike! I love Janet. Will you let me buy her?”

I said, “There’s nobody I would rather have a piece of my work.” So Francis bought Janet. And, I still hadn’t met him.’

A couple of years later I was doing a solo show at the inauguration of the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith.

I rang Francis and said, “Can I borrow Janet?”

He said, “Well, I’m loath to part with her. But if you need her … Anyway, she must be in the show.”

Six weeks later, after the show had finished, I sent Janet back. Francis telephoned, “I am so thrilled to have her back,” he told me. “And I have been thinking, would you do my portrait? A cloth head.” I said, “Oh God! I don’t know whether I can.”

I had never made a formal portrait. I would just play with cloth until things came out right.

He said, “Will you try?”

I said, “OK, I’ll have a go. But I’m a bit scared.” He said, “We’ll just see what happens.”

We arranged a sitting. He said “You come around. We’ll chat about it and we could have a sitting… ”

Our first sitting was in Bacon’s studio in Reece Mews. He peered down at me and said, “Come on up.” I went up the steps. It was like going up in a boat. He was peering through a hole in the floor. I was very nervous.

I’d heard that Bacon could be ‘difficult’.

But he was so nice. He had dressed up for the sitting, he had on a pale grey suit, with a blue cord shirt, and this big Rolex watch, and a lovely gold necklace. He looked absolutely fabulous.

The sitting began …

It was very easy. I wasn’t the kind of person who was going to get involved with Francis’s private life.

We were chatting, he told me a lot of his close friends had died. And he felt that he was feeling left behind, which was quite an intimate thing to tell me during the first sitting. But he was like that. He would just come out with what he was feeling. He mentioned George Dyer, his eyes just welled up with tears.

I have never been with someone whose emotions were so on the surface, and were so registering from minute to minute. Of course, it triggered my obsessive drawing – endless drawing.

He would ring me up whenever he wanted. We might not meet for a couple of months. But then we would meet up two or three times over a couple of weeks. Some times he would visit me in my studio, in Bloomsbury. I was in Bedford Square, and had a key to gardens, we used to walk and talk and then we would sit and I would do some sketches.

The cloth head was produced over four years.

He didn’t see the cloth head until I showed him to him in its completed form. He was very happy with it, and hung it beside Janet…

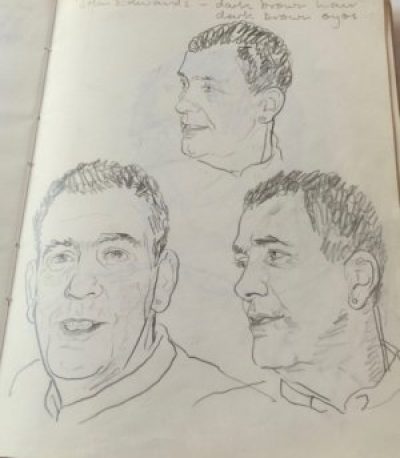

After that, we spoke a couple of times and we would see each other. I didn’t see much of him in his final years, but I did know his partner, John Edwards.

John called me after Francis’ death, and asked me if I would do a cloth head of him, so that he could hang it with the head of Francis and Janet, as a family…

© Shenstone Art

Clive Barker

Artist

Life Mask of Francis Bacon (1969) by Clive Barker

Clive Barker is England’s leading Pop Sculptor. He had formed a close friendship with Francis Bacon.

“I decided that I wanted to use Francis as the subject of a sculpture and came up with the idea of a life mask. I went to visit Francis at Reece Mews to discuss the possibility. My interest was sparked by somebody in Switzerland who had developed an exciting new formula for creating plaster that was much lighter than traditional recipes. The mixture had the consistency of porridge and when it cooled it was painted on the face. The advantage of this new method was that the lightness of the material meant that it did not sink into the face. Therefore, the features retained an astonishing likeness.

Francis willingly agreed to sit for the mask. I gave him two small straws to place in his nostrils so that he could breath and held his hand so that if he was in difficulty he could signal to me to stop. This was particularly important because after the initial layer was complete traditional plaster had to be applied over the top to ensure the mask retain its shape when it was removed. I was worried that the first cast might not have been successful but Francis reassured me that if that was the case he was happy to do it again. During the whole process Francis could only breathe through the two straws and after I had successfully completed the cast, he told me that he had been in agony because of his asthma. I felt terrible, but very touched by Francis’s support.

I went on to make six plaster and six bronze versions of the mask. There was a second edition of three further bronzes created when I went with Anthony D’Offay Gallery in London.”

© Whitford Fine Art, London MB Art Collection

© Whitford Fine Art, London MB Art Collection

© Whitford Fine Art, London MB Art Collection

© Whitford Fine Art, London MB Art Collection

© Whitford Fine Art, London MB Art Collection

© Whitford Fine Art, London MB Art Collection

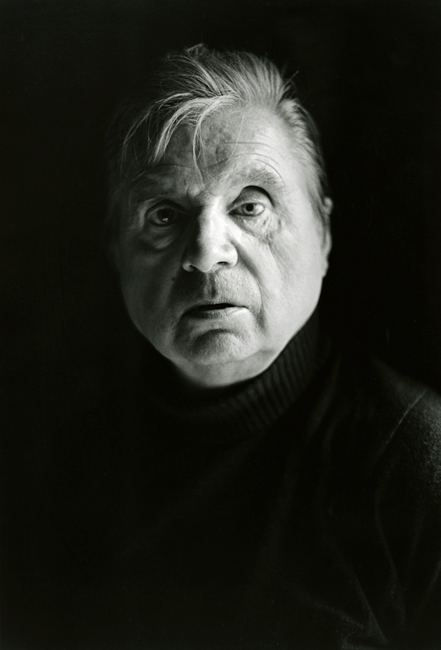

John Minihan

Photographer

Francis Bacon “Make Sense Who May”

Francis Bacon was a man whom I both knew and did not know. Born in Dublin in 1909, certainly Irish by birth, if not by blood. He had the Irish love for gambling, drinking and the perpetual desire to be somewhere else. I first met Bacon outside the Marlborough Magistrates Court, London 1971. The Daily Telegraph published a story ‘Irish Artist on Drug Charge’: the artist was acquitted. In his defence, he told the Magistrate that he could not have smoked cannabis found in his home because he was asthmatic.

Over the next 20 years I would photograph him on numerous occasions in London and, at his invitation, in Paris 1977 for his show at the Claude Bernard Gallery on the rue de Beaux Arts which became a busy street some 24 hours after the show’s opening had attracted, according to police estimate, 8000 viewers. Some six years earlier the French did him the great honour of putting on a retrospective show of his work at the Grand Palais. This is the kind of consecration that Bacon was accorded in a city that gave birth to photography in 1839 when Louis Daguerre exclaimed from the balcony, “I have seized the light, I have arrested its flight!”

Bacon came to love Paris from his first visit in the 1920s when he saw a show of paintings by Picasso which triggered in him the motivation to paint: like many others who have seen the paintings of Francis Bacon. You become either fascinated or repelled or both, by their power and effect on the emotions.

During the 1970s I would see Francis Bacon and exchange courtesies in Soho, London’s Bohemian Quarter with its strip joints, coffee shops and pubs. In those days Soho was full of drinking clubs. They existed partly to quench the thirst of afternoon drinkers, journalists, petty criminals, doctors, artists and writers at a time when the pubs were obliged to shut from 3 to 5.30pm. I remember those days very well. Working as a staff photographer for the Evening Standard in the early 60s, I spent much of my spare time in Ronnie Scott’s, The Marquee Club, The Colony Room and The York Minster, known now as The French.

I have fond memories of Francis sitting alone, a few years before he died, having lunch and liquid refreshment in the most exquisite Bibendum Restaurant in what was the Michelin Building at the intersection of the Fulham Road by the end of Pelham Street, a ten minute walk from the Bacon Studio at 7 Reece Mews, South Kensington. By that time I had photographed the artist many times in London and in Paris. It must be said that Valerie Beston from the Marlborough Fine Art, who Bacon trusted and depended on to make judgement on who he should and should not see, helped me to make contact with Bacon and Graham Sutherland whose wife Kathleen was Irish.

Bacon had given me his private home phone number. I remember calling him on the day of his retrospective at the Tate Gallery in 1985 and asking what time he would be at the Tate as I wanted to photograph him outside on the steps of what was then the original Tate Gallery, now renamed Tate Britain. As always, his manner over the phone was welcoming and he said I should be there about 2 o’clock, as he would arrive with friends. Francis arrived at the Tate just after 2 o’clock with friends Richard Chopping and Denis Wirth-Miller for what was then his second retrospective at the Tate Gallery. The press pack were already in the gallery. I was pleased to have my exclusive outside this illustrious building. All through the 80s I was photographing another Dubliner, Samuel Beckett, who was born some three years before Bacon. I became engulfed by Bacon and Beckett. They were hypnotic. I had hoped that I might get them both together in a photograph. I asked Francis who was very well aware of Beckett as Beckett was of Bacon. Francis Bacon told me that there were no messages in his paintings and no connection with Beckett. Like Beckett, he did not lie. David Sylvester the art critic created through his interviews with Bacon the cottage industry on which writers to this day so heavily depend. I remember having a pot of tea with David at the Dublin Writers Centre in 2001, after I took a photograph of him outside the Hugh Lane Gallery, he was telling me how photographers would approach him to take his picture in the hope that he would introduce them to Bacon. Many photographers did photograph the artist. He was happy in the company of photographers, less so with journalists. I do remember Bill Brandt telling me about his marvellous photograph of Francis Bacon on Primrose Hill, which Bacon told me some years later he hated. Photography was the salient influence in his work. He would often stop at the automatic photo booth in South Kensington tube station to pose for a strip of four passport sized portraits which he would work from. Recently in London I passed the now closed door that was the Colony Room, where once I heard the cry “Champagne for my real friends and real pain for my sham friends”, Bacon’s frequent toast which he displayed with an icy, ceremonious politeness.

Those who knew Francis Bacon are diminishing in number, at a time when exhibitions of his work worldwide are always a major artistic event. He would immortalise Muriel Belcher with his passion for triptychs in Three studies of Muriel Belcher (1966). Muriel was the greatest of Soho characters from 1948 when she opened the Colony Room Club. Francis Bacon would be her prized and most famous member. Like Samuel Beckett, Bacon had a bleak vision of human existence: where Beckett would write it, Bacon would paint it.

I want to thank Mr Majid Boustany founder and director of the Francis Bacon MB Art Foundation in Monaco for inviting me on a tour of the Foundation, which is a must for scholars and researchers interested in retrospective analysis of the artist. Among the items are letters, photographs, paintings, books about Bacon in all languages, and a Batchelors’s paint splattered butter beans can with assorted large brushes that were used to create a unique work of art with great inventiveness.

I did have a show of photographs, ‘Bacon, Beckett and Burroughs’ at the October Gallery, London February 1990. As we say in Ireland, ‘their likes we will never see again’.

John Minihan

Photographer

Photo and © John Minihan MB Art Collection.

Photo and © John Minihan MB Art Collection.

Photo and © John Minihan MB Art Collection.

Photo and © John Minihan MB Art Collection.

Caroline Cros

National Heritage Curator & Lecturer at the École du Louvre

Marcel Duchamp, an elective figure who links Francis Bacon to Richard Hamilton

“Perhaps I have nothing to do with the avant-garde. But I’ve never felt it at all necessary to try and create an absolutely specialized technique. I think the only man who didn’t limit himself tremendously by trying to change the technique was Duchamp, who did it enormously successfully.”[1]

Francis Bacon

In his interviews with David Sylvester, held between 1971 and 1973, Bacon discussed and praised the key figure of Marcel Duchamp. He notably evoked the “excellent” lecture the latter gave in Houston to the American Federation of Arts in April 1957.[2] During this talk, Duchamp stressed the “mediumistic” role of the artist. Bacon agreed with this approach, although preferred to refer to a “trance”. Duchamp defined the creative act as a dual emancipation: that of the artist, who finds his “clearing” and his path, and that of the spectator, who “brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.” Here too, Bacon approved. In the same interviews, Bacon interpreted Duchamp’s work through the question of figuration and abstraction, vaunting the French artist’s ability to produce images and signs that resist interpretation. “Most of Duchamp is figurative, but I think he made sort of symbols of the figurative. And he made, in a sense, a sort of myth of the twentieth century, but in terms of making a shorthand of figuration.”[3]

This capacity to step beyond the border of abstraction/figuration is what Bacon notably admired in Duchamp, saying that The Large Glass “takes to the limit this problem of abstraction and realism” like no other.[4] This “painting on glass” was undeniably a model for Bacon. Like Duchamp, but using “inherited techniques” – i.e., painting, photography and film – Bacon too managed to “produce something that differed radically from what these techniques had produced up till now”. In this way, Bacon placed his artistic practice in a very broad history of art, spanning several centuries of painting, with the ambition of setting himself apart from it, which was also one of the numerous achievements of Duchamp’s three masterpieces. Nude Descending a Staircase (1912), The Large Glass (1915–1923) and Etant Donnés (1946–1966) find their roots in Cranach’s nudes, Manet’s Olympia and several paintings by Ingres, Courbet and Picasso, while managing to transcend them, thereby writing a new chapter in the history of modern art.

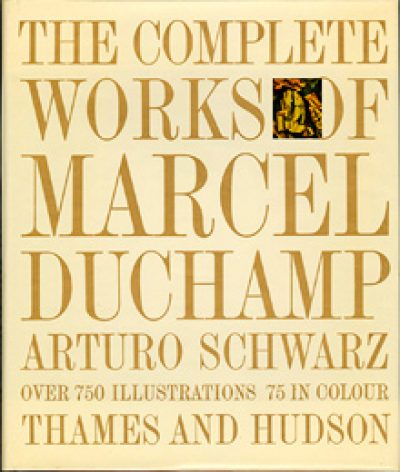

In 1966, the Tate Gallery in London held the first European retrospective of Marcel Duchamp, The Almost Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, for which the English artist Richard Hamilton, who curated the exhibition, executed the first reproduction of The Large Glass, the exact title for which is The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even. During these years, Bacon and Hamilton spent time together and shared a mutual admiration for Duchamp. Bacon visited the exhibition and purchased one of the first editions of the catalogue raisonné of Duchamp’s work, published in the UK in 1969 by the art dealer Arturo Schwarz. From 1968 to 1970, Francis Bacon and Richard Hamilton frequently lunched together. Hamilton would ask his artist friends to take a picture of him with a simple Polaroid camera, and the result is a series of portraits of Hamilton by Bacon, testifying to their friendship. This series of six studies, dated 1970 and entitled Portrait of the Artist by Francis Bacon, is really a four-handed work. One of these portraits, chosen by Bacon, would go on to be printed and published numerous times: “I also suggested to Francis Bacon that an interesting print might be produced from a photograph he made.” This question of collaboration is also central to Duchamp’s approach – one thinks notably of the numerous portraits of Duchamp by Man Ray. As an avid connoisseur of Duchamp, Hamilton obviously had these examples in mind.[5]

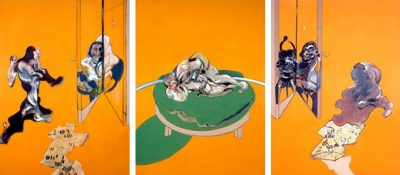

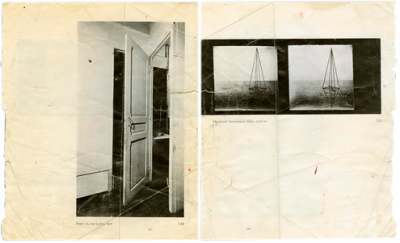

At the opening of the Bacon exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris in 1971, and the ensuing dinner at the Train Bleu restaurant at the Gare de Lyon, Richard Hamilton and Teeny Duchamp were present alongside Bacon and a number of leading French (Marguerite Duras, Michel Leiris) and English personalities (David Hockney). Hamilton, who deciphered Duchamp’s The Large Glass and Notes, was undeniably the link between these two figures who seem so far removed. Alongside the first edition of the catalogue raisonné of Duchamp’s work by Arturo Schwarz (Thames & Hudson, 1969), in his studio on Reece Mews, Bacon compiled several press cuttings from the 1970s representing Nude Descending a Staircase (1912) and his friend Richard Hamilton’s reproduction of The Large Glass (1915–1923). Among these pictures, which formed Bacon’s “iconographic compost”, his “inner camera obscura”, featured the black and white reproduction of two of Duchamp’s works – rather abstract and far less famous than The Large Glass and Nude Descending a Staircase: Door, 11 rue Larrey, 1927, the door in the studio on rue Larrey in Paris, where Duchamp lived from 1927 to 1942. Since his studio was too narrow, the artist created a corner door that served to open and close the bathroom on one side and the bedroom on the other. Open and closed at one and the same time,[6] this door reappears in Bacon’s triptych, Studies from the Human Body, dated 1970. The left and right parts of the triptych are inhabited by this motif of the corner door, which in Bacon becomes a reflective surface: on the left side, the female model becomes lost in an endless reflection in it. On the right side, the door is ajar and reflects a dual image: a male character, probably Bacon, and an anthropomorphic camera standing on a tripod. Part animal, part human, the form of this camera also seems to come from a surrealist painting by Picasso, Joan Miró, Max Ernst or Wilfredo Lam. Another work by Duchamp, Handmade Stereopticon Slide, executed between 1918 and 1919 during his stay in Buenos Aires, returns in a second triptych by Bacon: Three Studies of the Male Back, 1970, preserved at the Kunsthaus, Zurich.

In both cases, Bacon has taken these works out of their context. He has neutralised their history, origin and symbolic meaning to recycle them without copying them nor commenting on them. Using sources as diverse as press cuttings, scientific articles on diseases, madness, Muybridge’s chronophotographs, animal life and combat sports – as well as artistic references such as Cimabue, Velasquez, Rembrandt, Van Gogh and Picasso, of course, but also Max Beckmann – Bacon, like Warhol,[7] no doubt his true postmodern heir, devoured images. His memory worked like a fearsome and tireless machine, forever scrutinising and ingesting. Some, like Deleuze, would refer to a “rhizome”, others to an “exquisite corpse”, or more recently to Creolisation. An anthropologist of images, an iconoclast and an informed historian, Bacon accumulated, digested and recomposed endless encyclopaedic sources; contrary to all expectations, Duchamp holds a privileged place in his work.

Caroline Cros

National Heritage Curator and Lecturer at the École du Louvre

[1] David Sylvester, The Brutality of Fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon (London: Thames & Hudson, 1987), p. 107.

[2] Marcel Duchamp, Le Processus créatif, Paris, l’Échoppe, 1987.

[3] Interviews with Francis Bacon, p. 105.

[4] Ibid. p. 179.

[5] Richard Hamilton, Interactions: Marcel Duchamp, Francis Bacon, Sherrill F. Martin, Dieter Roth, Lux Corporation, Ohio Scientific (Stockholm: Thordén Wetterling Galleries, 1987), p. 6. “From time to time, since 1968, I have been wont to offer a Polaroid camera to artist friends with the request to take a photograph of me… One of the interests in indulging in this activity is to find that the results can sometimes bear a strong relationship to the visual sensibility of the person pressing the button. This was strikingly seen in a Polaroid of me taken by Francis Bacon. It was not the shot that he chose to be reproduced in the book but it seemed to me to be extraordinary like his paintings.”

[6] Le Corbusier also used this principle for the Villa La Roche in Paris, circa 1925.

[7] He often visited the New York Public Library, particularly the “Picture Collection” department, to obtain pictorial sources.

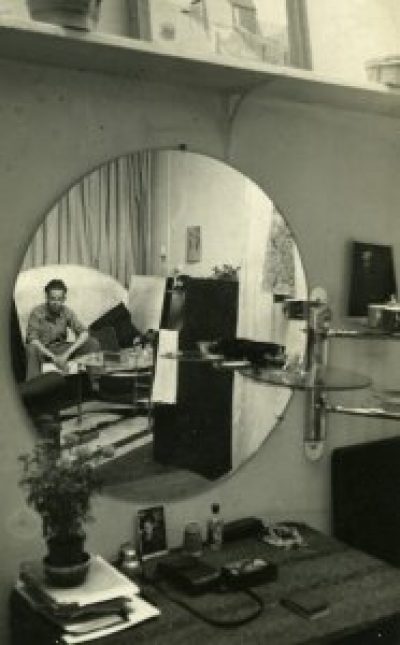

Carlos Freire

Photographer

Francis Bacon, Encounters

It was 1977 the first time I met Francis Bacon, in Paris, in a bar on Rue des Beaux-Arts. Another time, I went to his studio in London that same year for a photo shoot. The third and last time we saw each other was in London again, at his studio and at the Marlborough. Afterwards we went for lunch at Wheeler’s in Soho. On these occasions I took several photographs of him – he was a relaxed subject.

When I’m asked about the times I met Bacon, people mostly want to know about the subjects we discussed. We talked about painting, photography, about his Parisian friends too – among them Michel Leiris.

There was never any difficulty photographing him. He was there, present, available.

Francis Bacon was a great painter and cultured, which everyone knows. To my mind he was also a gentleman. Open to agreeing to have a novice photographer like myself in his studio.

Mission accomplished, according to Marc Fumaroli in his publication Célébrations, la poétique de Carlos Freire: “The photos of Carlos Freire have immediately proven to be a superb and violent elegy, the most accurate gloss of Bacon’s paintings and his end-of-an-art poetry.”

It is Majid Boustany’s sharp eye that recognised the singular and rare quality in my photos, which was an essential criterion for their being included in the collection at the Francis Bacon MB Art Foundation in Monaco. They are very much at home in this rare and unique place.

November 2014, Paris

Paul Rousseau

The John Deakin Archive

John Deakin: Wheeler’s Lunch

The John Deakin photograph “Wheeler’s Lunch” is not all it seems.

Taken in his favourite seafood restaurant, Francis Bacon appears the main focus, Christ-like in the centre, under a wall plate halo. The forward-facing arrangement alludes to its other title: “Last Supper”, a nod to the irreligious Bacon, but framed by a lapsed catholic, Deakin.

Deakin dated the print to March ’63, and in December 2014 Catherine Lampert asked Frank Auerbach for his memory of the event. He recalled they assembled grumpily at 11am, and that the image was an unused commission for Queen magazine by Francis Wyndham. Bill Feaver reports that Freud, Auerbach and Andrews all confirmed no actual ‘lunch’ took place, which rather destroys the illusion, as does a closer look at the champagne bottle – unopened.

Whatever the motive, the cultural significance must have been obvious to Deakin: he was capturing the major British painters all together as friends in their natural habitat of Soho. But its more personal value to Deakin is touchingly reflected by the three rolls of film he shakily used up, taking 36 shots of one scene, and later by his arranging for them all to sign the mounted print, like a fan collecting autographs.

For the Francis Bacon MB Art Foundation monthly focus, The John Deakin Archive is pleased to present here for the first time an animated sequence of the best negatives, bringing the occasion back to life. Exposing mini-narratives and new insights, we see Bacon expresses a subtle stiff-backed ‘camp’, and seems in collusion with Freud. In one frame Freud shoots Bacon his signature wide-eyed stare, which Bill Feaver claims is the only photograph to capture it. Auerbach and Andrews appear relaxed and share a joke, Behrens fidgets, nervous and uncomfortable. They look out at us, laugh, sip water and smoke.

No bread or wine taken at this last supper.

© The John Deakin Archive

Dr Rebecca Daniels

Art Historical Researcher on The Francis Bacon Catalogue Raisonné

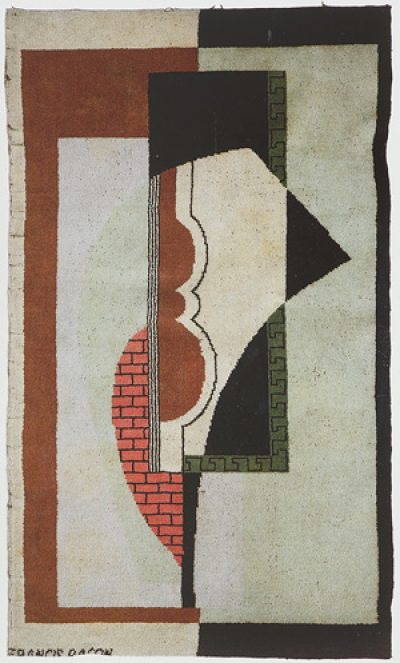

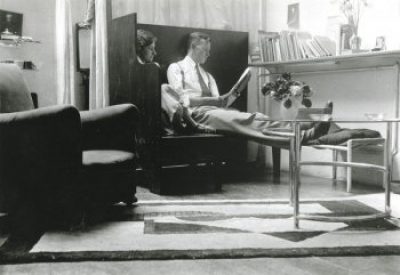

Rug by Francis Bacon

In 1929 after an extended sojourn in Paris possibly working as a designer, the young and entrepreneurial Francis Bacon was busy designing rugs, furniture and paintings for an exhibition he was to hold in November 1930 at his studio at 17 Queensberry Mews West, South Kensington, London.

This highly important rug is a rare survivor from that period. The geometric design captures the zeitgeist of progressive modernist rugs produced in England by McKnight Kauffer and Marian Dorn as well as absorbing the art of Cubism, de Chirico, Léger and Jean Lurçat. Bacon provides important documentary evidence about the rug in a statement dated 9 December 1983: ‘this is a rug designed by me in 1929 and made up by Wiltons’. It is the only primary evidence that exists relating to any of Bacon’s rugs and confirms the long held belief that they were manufactured by the famous Wilton Carpet Factory. One could argue that this was one of Bacon’s favourite rugs as it is included, along with a sofa and coffee table also of his own design, in photographs of his living room taken at Carlyle Studios in Chelsea, London, in c.1932. The principal motifs in the rug, the stylized string instrument and the brickwork, also appear in one of his earliest works on paper, ‘Gouache’ (1929). The close visual relationship between the rugs and paintings displayed in the 1930 exhibition was commented on in an unidentified newspaper review: the paintings ‘main raison d’etre’ it was observed was ‘being the decorative purpose which they serve in a general scheme of interior decoration’. It also suggests that Bacon’s interior design was an important starting point in his transformation into one of the greatest painters of the 20th century.

MB Art Collection

Photograph by Eric Megaw

Photo: Eric Megaw

Photo: Eric Megaw

Katharina Günther

Art Historian

Working material: Bullfighting

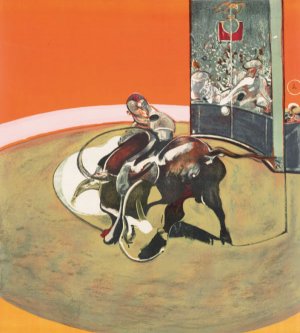

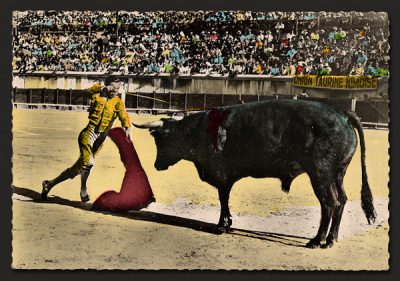

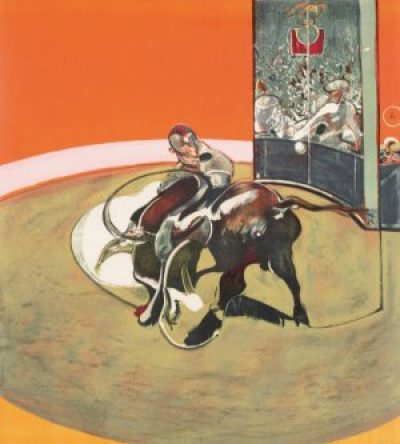

Francis Bacon was fascinated by bullfighting, which he famously regarded as ‘a marvellous aperitif to sex’. The cruel sport features directly in paintings from the late 1960s, such as Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne Standing in a Street in Soho, 1967 and Study for Bullfight No. I, 1969.

Bacon had ample opportunity to visit the corrida on his extensive travels to the South of France and Spain and his vast collection of books and postcards on that topic echo his strong interest. The hand-coloured postcard of a bullfighter attacking the animal head-on was found in his studio at Reece Mews, London. The banner on the stands saying ‘Union Taurine Nîmoise’ suggests that the picture was taken in the historical Arena of Nîmes, which is still used as a bullring today. It is easily conceivable that Bacon bought it there himself.

This working material decisively informed Bacon’s imagery but, surprisingly, the painted subject is not always related to that of its source. It was recently discovered that a photograph of a matador dressing up for the arena from Robert Daley’s book ‘The Swords of Spain’ formed the basis of Bacon’s Study for Portrait of Gilbert de Botton, 1986.

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. Collection: Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane (RM98BC5)

Martin Harrison

Editor of The Francis Bacon Catalogue Raisonné

Painting 1946

In July 1946 Bacon’s Painting 1946 made its public debut at the Redfern Gallery, London. It was, particularly in the context of post-war British art, exceptionally large and ambitious; one critic compared Bacon’s technique with Velázquez, but The Times correspondent thought it the ‘most alarming’ picture in the exhibition and its imagery was widely perceived as provocative and disturbing. It was bought for £200 by Erica Brausen, but immediately after selling the painting Bacon left London for Monaco. He lived in Monaco for most of the following three years, and continued to return there regularly throughout his life.

Although Bacon was deeply critical of all artists’ work, including his own, evidently he regarded Painting 1946 as a significant achievement. It was the first of his paintings to be bought by a museum, and its purchase by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1948, was an important milestone in his career.

For Bacon one of the main precepts that propelled his paintings was the operation of ‘chance’. He considered that Painting 1946, which he said ‘came about entirely by accident’, epitomised this. Even forty-five years later, in one of his last interviews, he continued to cite Painting 1946 in order to demonstrate how his imagery arose by chance. Recent scholarship, however, has shown that its iconography was more premeditated than Bacon had suggested, and research on this topic is proving to be a fertile aspect of modern Bacon studies.